Die tote Stadt (The Dead City) 101 – Music Style

By: Betsy Schwarm

Given its blend of music, words, and stage action, opera can be a powerful tool for psychological exploration. It is not just a matter of what these characters are doing, but why they are doing it, and how they feel about themselves and their lives. Their inner selves become more vividly available with finely crafted music to express those feelings. The characters are fictional, but the music can make them seem almost real.

Interested in learning more about Die tote Stadt‘s plot and characters? Check out earlier installments of Die tote Stadt (The Dead City) 101:

KORNGOLD: A GIFTED COMPOSER

From Mozart to Puccini, many composers have worked to do more with their operas than just tell a story. But the results are even more compelling in the instance of Die tote Stadt, which combines a particularly young mind (Korngold was just 23 years old in 1920) living and working in the city of Vienna, where Freud was exploring the inner self. Freud’s developing theories about the power of the unconscious permeated arts and culture.

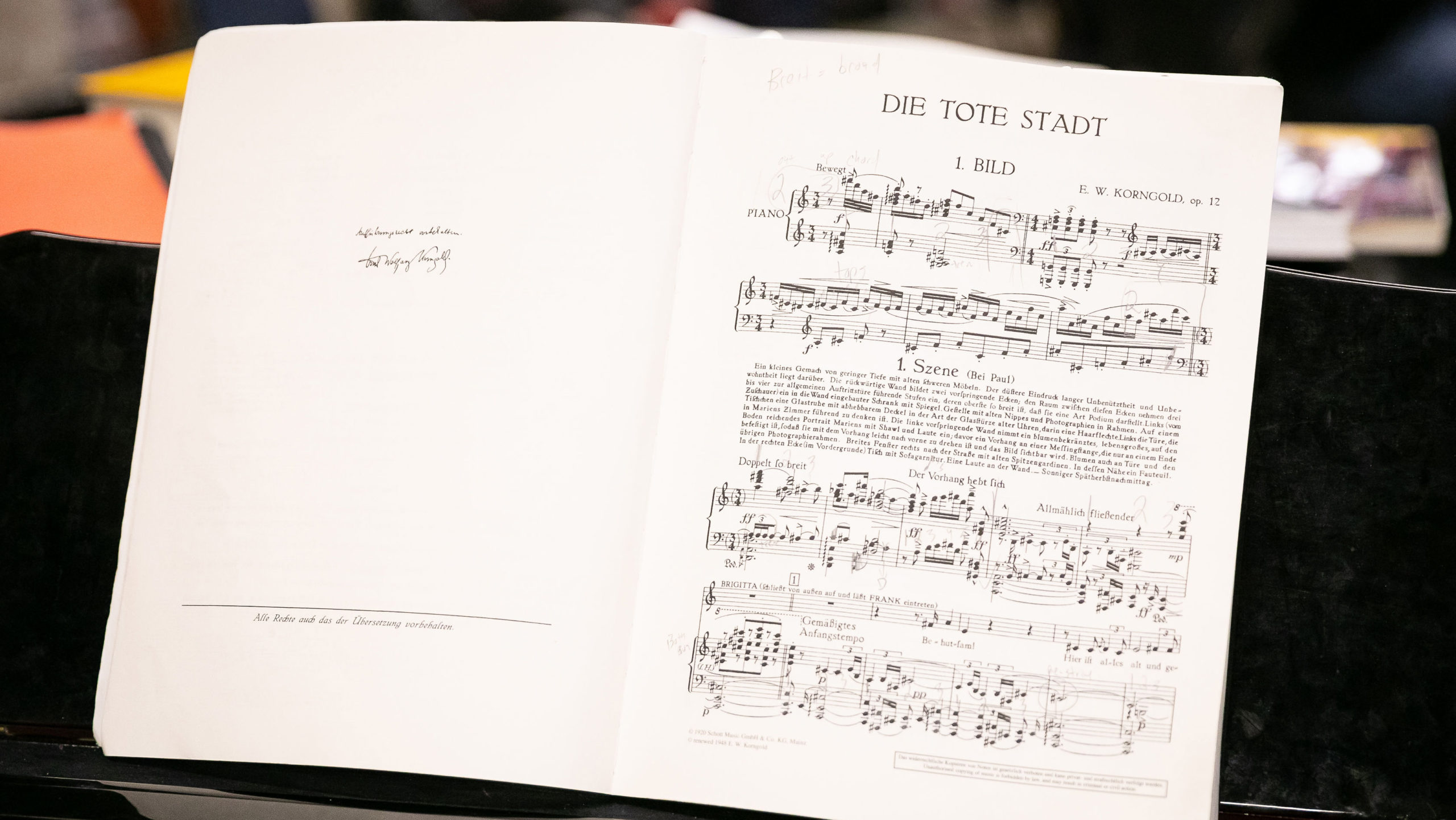

Korngold’s father, one of Vienna’s most eminent music critics, gifted his son a middle name which paid tribute to Mozart. The younger Korngold rapidly became the toast of Viennese musical society, which gratified his father. Die tote Stadt was already Erich’s third opera—not just the third he’d written, but the third to reach the public. At its December 12, 1920, premiere, some may have been startled by the excellence of its craftsmanship. However, those who had been paying attention to headlines would have known they were likely to find the opera to be a remarkable experience.

Learn more about the composer Erich Korngold through his bio>>

BREAKING DOWN THE SYMBOLISM

Photo: Matthew Staver

To enjoy this opera, it is helpful to have an explanation of the title, meaning “the dead city.” This is not a city where the undead walk the streets. Only Marie is dead, and she haunts just one individual, her widower Paul, who cannot get her out of his thoughts let alone his heart. Korngold borrowed the tale from Belgian writer Georges Rodenbach (1855 – 1898), whose 1892 novella Bruges le morte (Bruges the Dead) had been a Symbolist landmark. But what exactly does “the dead city” symbolize? It might help to know that Rodenbach illustrated his tale with photographs of the actual city of Bruges, perhaps more interested in its past than in its future. Beyond the name of the opera hinting at the character’s inability to move forward, music, too, can underscore ways of reading the characters, allowing listeners to sense what troubles and motivates them.

Chas Rader-Shieber, director of Opera Colorado’s production, observes that Korngold’s opera exists in “a surreal landscape of items that have their own life and sometimes suggest other realms and places.” Paul’s obsession with his memories of Marie “begins to blur the lines between reality and fantasy.” Has she been restored to life, or is it only Paul’s imagination? Are his actions what the character actually does, or just scenes from his subconscious? Rader-Shieber describes the shifting perspectives as “both thrilling and terrifying.” Are we to pity Paul, or loathe him? Therein lies the director’s task, though it was initially Korngold’s.

THE MUSICAL STYLE OF DIE TOTE STADT

Photo: Matthew Staver

Forming that musical connection with the characters is part of the power of opera, and Korngold sets about it early in Die tote Stadt. In Paul’s act one aria “Glück das mir verblieb,” he muses with rapturous longing on love that survives. He imagines (or hears) Marie’s voice, which colors his feelings: gentle melancholy, but not anguish. The latter lies in Paul’s future, but first Korngold sought to give audience members a glimpse of the protagonist’s heart.

Paul’s friends and neighbors have a different, more cheerful reading on the world. In act two, they enjoy an exuberant boating party. Amongst the convivial gathering is the dancer Marietta, whom Paul is half convinced is his own Marie reborn. Bruges’ canals may not be those of Venice, but that does not mean one cannot sing spiritedly to the night sky. Their jovial voices—the only entirely festive music of the opera—provide a striking contrast to Paul’s troubled heart.

Bruges itself also has a musical voice. Frequently, one hears the tolling of bells, suggesting the church towers visible in the photographs found in the original novella. Additionally, the orchestra includes a wind machine, and, at times, Korngold calls for off-stage voices and sounds. Are they actually part of the scene, or is Paul imagining them? That distinction is largely left to the listener, or at least the director.

KORNGOLD’S INFLUENCE

Die tote Stadt isn’t the first twentieth-century opera; at the very least, it was predated by Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904). However, the psychological aspects of the tale are reflective of its time. Emotional coloring would serve Korngold well in the last half of his career, which he spent in Hollywood, showing American composers how to write better for cinema. What Korngold had learned with Die tote Stadt served him quite well on the silver screen.

Program notes by Betsy Schwarm, author of the Classical Music Insights series.